A riveting historical drama of the first published rape trial in American history and its long, shattering aftermath.

More than two hundred years later, so much has changed.

So much has not.

A New York Times Editor’s Choice.

Winner of the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, the James Bradford Best Biography Prize, the Gotham Book Award, the Langum Prize in American Legal History, and the New York City Book Award.

The Journal of the American Revolution’s Book of the Year.

On a moonless night in the summer of 1793 a crime in the back room of a New York brothel transformed Lanah Sawyer’s life. It was the kind of crime that even victims usually kept secret. Instead, the seventeen-year-old seamstress did what virtually no one else dared to do: she charged a gentleman with rape. The trial rocked the city and nearly cost Lanah her life.

And that was just the start.

Based on extraordinary historical detective work, Lanah Sawyer’s story takes us from a chance encounter in the street into the squalor of the city’s sexual underworld, the sanctuaries of the elite, and the despair of its debtors’ prison—a world where reality was always threatened by hope and deceit. It reveals how much has changed over the past two centuries—and how much has not.

News & Reviews

Readers, critics, and journalists have responded to the Sewing Girl’s Tale with enthusiasm. For a roundup of early reviews, see the Aug. 12, 2022 edition of The Week.

The book was featured on the cover of the New York Times Book Review, where it was reviewed by Tali Farhadian Weinstein, a former federal and state prosecutor. She describes The Sewing Girl’s Tale as “excellent and absorbing,” emphasizes its broad contemporary relevance, and concludes that its ending (which involves Alexander Hamilton’s notorious Reynolds Affair) is “emblematic of the delights to be found in this book, despite its grim subject.”

The Atlanta Journal Constitution praised the Sewing Girl’s Tale as “a historical retelling that is decidedly pro-woman....fascinating.” The Minneapolis Star Tribune described it as “a masterful and sweeping account of life in 1790s America.”

“A masterpiece,” raved Fergus M. Bordewich in the Wall Street Journal. “The Sewing Girl opens a window on the tumultuous world of the early republic. What we see is in some respects lurid and shocking, but it also delivers a vividly intimate portrait of American life as the nation was coming into being.”

Library Journal, in a starred review, hailed The Sewing Girl’s Tale as “An engrossing, historical, true crime narrative.” Their verdict? “An important and highly readable addition to the history of crime and sexual politics in America that will be of interest to historians, women-focused history researchers, sociologists, and fans of true crime.”

For more reviews, see Booklist, Publishers Weekly, Kirkus, and the The Times of London.

Personal testimonials from readers can be found here.

The Audiobook

Gabra Zackman’s narration of The Sewing Girl’s Tale is pitch perfect. Zackman, also known as the “the audiobook goddess,” has won many awards for her audiobooks and is listed as one of Audible’s Ten Best Female Narrators to Listen To Now. Check out a clip below or here.

Hot off the press!

Read an illustrated essay on Lanah Sawyer’s clothing and forensic evidence in Commonplace.

Or, check out an excerpt from the book on “Sex, Love, and Rape Culture in Early America” on LitHub.

About John

I’m an American historian and former director of UNC Chapel Hill's Program in Sexuality Studies—and, for that matter, former newspaper delivery boy, gardener, library page, pizza maker, park ranger, gas station attendant, owner of a bee-keeping supply start-up, and tourguide at the house in which Louisa May Alcott wrote Little Women.

As an historian, I've spent my career trying to understand the lives of people in early American history who weren’t well known at the time and didn’t leave much of a trace in the surviving documentary record. Putting them at the center of the story changes our understanding of the past—and the present.

In writing the Sewing Girl’s Tale, which focuses on a survivor of a sexual assault, it was especially important to keep her at the center of the story—and to make it clear that her story began long before the assault and continued long afterwards. Ultimately, I wanted to know: What was life in the aftermath of the American Revolution like—not for some Founding Father—but for an ordinary young woman, a seventeen-year-old seamstress, struggling to make her way in a world full of possibility and danger.

A more formal academic bio

John Wood Sweet is a professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and former director of UNC’s Program in Sexuality Studies. He graduated from Amherst College (summa cum laude) and earned his Ph.D. in History at Princeton University. His first book, Bodies Politic: Negotiating Race in the American North, was a finalist for the Frederick Douglass Prize. He has served as a Distinguished Lecturer for the Organization of American Historians, and his work has been supported by fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Mellon Foundation, the National Humanities Center, the Institute for Arts and Humanities at UNC, the Gilder Lehrman Center at Yale, the McNeil Center at Penn, and the Center for Global Studies in Culture, Power, and History at Johns Hopkins. He lives in Chapel Hill with his husband, son, daughter, and a new baby.

My Search for Lanah Sawyer’s Story

For many years I thought I understood Lanah Sawyer’s story. Three decades ago, when I was working on my Ph.D. in history, one of my professors, the celebrated women’s historian Christine Stansell, introduced me to William Wyche’s Report of the Trial of Harry Bedlow, for the Rape of Lanah Sawyer (New York, 1793)—the first published report of an American rape trial. (To read it, click here.)

It was a gripping courtroom drama—by turns anguishing, exciting, and infuriating. Even then, the parallels between Lanah Sawyer’s case and the enduring dynamics of date rape were obvious and haunting. Two of my fellow graduate students, Marybeth Hamilton and Sharon Block, published brilliant studies of the case in light of broader historical patterns. So, when I began teaching I often used the case to help students explore the historical roots of modern rape culture.

Then, about twelve years ago, a graduate student I was working with, L. Maren Wood, shared a reference she had discovered in a New York newspaper, five years after the rape trial. It was a summary of an affidavit—in which Lanah Sawyer retracted her charge of rape. Curious, I tracked down the full version of the purported retraction, which had been published in a newspaper in, of all places, Poughkeepsie. It threw my assumptions about the case into doubt. And it made it clear that the story didn’t end with the rape trial: it went on for years afterwards and was much more complex than I had imagined.

Curious, I set aside the book I was working on at the time. What actually had happened? I wanted to know. What really was Lanah Sawyer’s story?

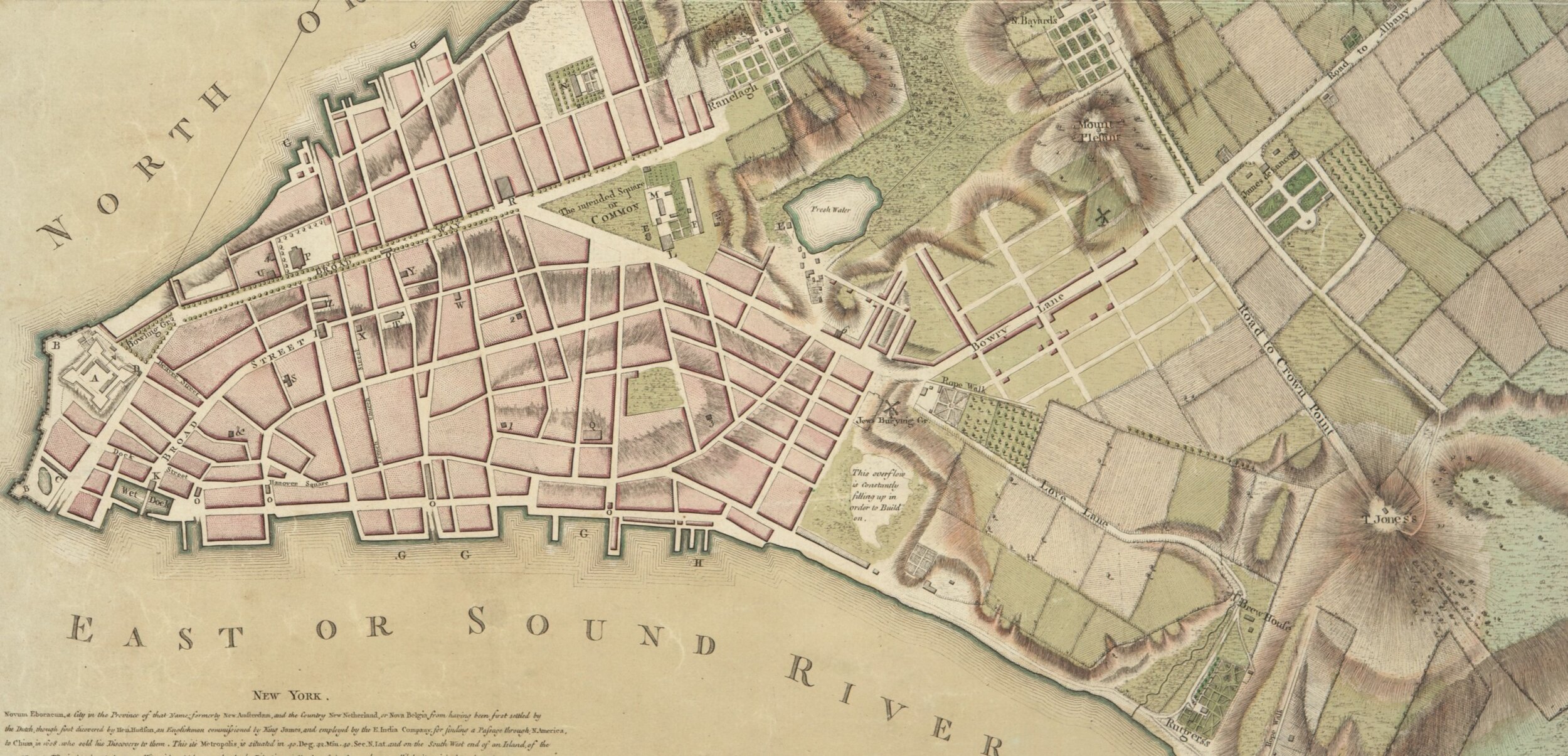

I spent more than a decade searching out evidence—long lost trial minutes; records of every sexual assault prosecutions in Manhattan for almost a century and dozens of civil lawsuits for seduction; contemporary newspapers, letters, diaries, account books, novels, land records, maps, watercolors, engravings, portraits, silverware, and even a carriage; sewing cases, samplers, dresses, undergarments, and accessories (including bum rolls)—piecing together what I discovered, and puzzling over what it all added up to.

The result is this book: The Sewing Girl’s Tale.

“How do you know that?”

Glad you asked! Here are a few answers.

What did Lanah Sawyer wear?

Who lived where?

What happened in court?

Resources for scholars, teachers & serious history geeks

Q & A

In conversation with John about the book

-

In this book, I explore the momentous period after the American Revolution not through the eyes of the so-called Founding Fathers but rather through the eyes of an ordinary New Yorker: a seventeen-year-old seamstress named Lanah Sawyer. Today, most people have never heard of her. And if she hadn’t responded to a sexual assault in a really unusual way, she might have left no trace at all. For historians, accessing the perspectives of ordinary people—working people, women, youths—is notoriously difficult. It takes perseverance and patience, and luck. But I’ve spent my entire career trying to tell stories that others used to say could not be told.

For The Sewing Girl’s Tale, I wanted to do more than figure out what actually happened. I wanted readers to be able to visualize the city Lanah Sawyer inhabited, to understand how her world worked, and to appreciate the challenges she faced, her fateful decisions, her courage, her heartbreak.

What emerged was a story not from the top down but from the bottom up: a story of a young woman looking to make her own way in a city full of possibility and danger; a story of working men fed up with being disparaged and dismissed; and a story of early feminists making bold new arguments about human rights at a time when the only way most single women could earn a living wage was by working as a prostitute.

-

I’ve spent my career studying and teaching early American history, but this project kept throwing me for a loop.

I was surprised by what I learned about Lanah Sawyer’s family. I was surprised by the big business of prostitution. I was surprised by the disparity between how romance was idealized in the novels of the day—and how courtship actually worked in real life. I was surprised by the audacity of the defense lawyers during the rape trial and by their blatant efforts to rewrite the law. I was surprised by the public response to the jury verdict–which included riots in the streets. I was surprised by the forceful feminists who raised their voices to call out sexual double standards. I was surprised that Lanah Sawyer ended up securing meaningful legal recourse. I was surprised that the perpetrator, Henry Bedlow, ended up in debtors’ prison. I was surprised by the scurrilous tactics employed by his attorney, Alexander Hamilton.

And, call me naive, but I was surprised every time I caught someone lying.

What was most surprising, in the end, was that the more I learned about the dynamics of sexual assault today, the more modern and tragic this story became. So much of this story could have taken place on a college campus today. We still live in a startlingly similar culture of sexual predation and impunity. This immediacy is part of what makes Lanah Sawyer’s story so inspiring and gut-wrenching.

This story feels unsettling and disorienting now, I think, because in this time so long ago, in this case, so much of our modern gender system and legal culture were being created.

-

In The Sewing Girl’s Tale, we see Alexander Hamilton just after his stint as secretary of the treasury, back in New York, working as a practicing attorney—and what we see is pretty ugly. At a crucial turning point in this story, Hamilton was hired by the family of the perpetrator, Henry Bedlow, to get him out of a serious pickle. And, as an attorney, Hamilton was clearly smart and effective. But the methods he used in this case were, frankly, fraudulent and cruel.

Anyone familiar with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s brilliant musical or Ron Chernow’s engrossing biography knows that Hamilton was involved in a scandal called the Reynolds Affair—involving sex and crime, money and secrets, betrayal and fraud. Hamilton’s work for Henry Bedlow puts that scandal in a new light. Ultimately, I think in their willingness to defend their own honor at any cost either to themselves or others, Hamilton and Bedlow fed each other’s darkest impulses.

-

The gown Lanah Sawyer wore on the evening she was raped is an example of how consulting with experts opened my eyes and led to stunning revelations. During the trial, the dress was the only piece of forensic evidence. The prosecution used it to support Lanah’s testimony about how Bedlow had torn it during the assault and how, the next morning, she had sewn it back together.

At first, I was simply curious about what the gown looked like. But this was a period of transition in women’s fashion and there was only so far published guides could get me, so I turned to a number of leading experts for help.

During one meeting, Linda Baumgarten, the textile curator at Colonial Williamsburg, patiently answered my questions. Then she offered two observations.

First, she said, there was no need for Henry Bedlow to remove Lanah’s gown if intercourse had been his only goal: women in this period did not wear drawers, so he could have just pulled up her skirts. The fact that he wanted Lanah naked says something about his sexual aim.

Second, Baumgarten pointed out, the fact that the gown was torn supported Lanah’s account of a violent struggle. Clothing was expensive; she was probably proud of this gown. If she had removed it voluntarily, she would have been careful. The damage indicates that it was removed against her will.

So, I started out looking for a simple description and ended up with two powerful insights into the very nature of the assault.

-

I think we all read stories for a variety of reasons: to get lost in a narrative, to learn about important issues, to cultivate empathy, to make sense of our world, and, most profoundly, to change the way we think and feel.

I have worked on this project for more than ten years, trying to learn about her life, her experiences, her reactions. But I didn’t anticipate the ways it would change me.

Early on, I noticed that at the heart of this project was an uncanny kind of double-vision. At every turn, as I struggled to bring Lanah Sawyer’s long lost world into focus, I saw, at the same moment, the world we inhabit today. In Lanah Sawyer, I see all of the friends, relatives, acquaintances, co-workers, and students who have shared their own stories with me. And I see moments in my own life.

For me, the process of keeping Lanah’s story always in focus, always at the center, for so long has made this project feel intimate and intense and transformative. It has encouraged me to honor my own experience, to recognize moments in my own life that I usually keep compartmentalized and tend to dismiss.

We live with so much exploitation and harassment, so much shame and silence. There is triumph in this story as well as tragedy, and there is also a kind of solace. So maybe this book is an invitation to us all to take our own lives seriously, to trust in ourselves.

-

Lanah Sawyer’s story shows the importance of the modern distinction between fear of “stranger danger” and the realities of acquaintance rape—a distinction that this rape trial helped create.

Her story opens with her walking down Broadway: she’s harassed by a group of foreign men but a seemingly gallant “gentleman” steps in to rescue her. He insinuates himself into her confidence and entices her out on a date. Only when it’s too late does she realize that her “fine new beau”—not the strangers in the street—was the real threat.

Today it’s much the same: our fear of strangers helps disguise the fact that most sexual assaults are perpetrated by acquaintances: a cousin, a boss, a teacher, a guy at a party.

During the rape trial, the defense lawyers seized on earlier legal commentaries and exaggerated their implications. Their goal was to redefine rape in terms of physical violence rather than consent and to convince the jury that Lanah Sawyer wasn’t someone who mattered.

The result was to characterize “real” (or stranger) rape as a violent, surprise assault perpetrated by a man of lower social standing—a cultural script powerfully weaponized by American white supremacists against Black men.

Conversely, whatever an acquaintance might do—whatever a date like Henry Bedlow might do—couldn’t be rape. In such scenarios the means of coercion involve so much more than physical force: assailants target victims, misdirect and isolate them to render them vulnerable, leverage their social authority, and exploit their victim’s confusion, fear, and sexual shame. Victims typically don’t report such crimes—in part because they have been rendered agonizingly difficult to prosecute.

Lanah’s story illuminates how this bifurcation of stranger/acquaintance rape came into being—and why it matters.

-

In the 1790s, the city of New York was at the forefront of a titanic struggle over the destiny of the American republic.

When Lanah Sawyer faced off against Henry Bedlow in court, many saw it as part of a larger conflict between champions of democracy and defenders of aristocracy. At the time, many of the Founding Fathers considered democracy a dangerous idea; they argued that elite men should run the country and everyone else should know their place. But by 1793, the French Revolution had presented a much more radical vision of equality—which some saw as an inspiration and others as a nightmare.

This story was set in motion by a miscalculation on Henry Bedlow’s part. He clearly assumed that he could use his elite status to attract the attention of Lanah Sawyer and that she, given her modest social standing, wouldn’t dare stand up to him. But she did.

During the trial, Bedlow’s lawyers also used Lanah’s class status to disparage and dismiss her. “What else,” one of them sneered, “did she imagine a gentleman like him wanted with a sewing girl like her?” They seemed to judge the jury correctly. But no one could have anticipated that their elitism and scorn would provoke such widespread outrage.

And so this case became not just about women and their rights but also about working men and their right to dignity, and respect, and justice.

-

I think that when Henry Bedlow decided to target Lanah Sawyer he underestimated not just her but also her family. And I think he assumed that her working-class stepfather wouldn’t have the gumption, or the resources, to take on a rich and well-connected man like himself. But he was wrong. Lanah’s stepfather, John Callanan, turned out to be a man of remarkable grit, determination, and legal savvy.

At the same time, Callanan was not simply Lanah’s ally. After she was assaulted, Lanah desperately wanted to go home but was afraid that he would beat her without listening to what had happened. And it’s clear that her fear was well-founded. In the end, she managed her return home in a way that did get him to listen to her story and got him on her side. And he turned out to be a remarkably effective champion.

This same process was repeated over and over. Time and again she had to win over potential allies. And time and again she did. So I think she did exercise a lot of agency in shaping how her story unfolded. At the same time, alliances always involve some loss of control.

And there’s a fine line between alliance and appropriation. I think Lanah always faced the danger that others might not just take on her cause but also take it over.

-

First, in American history, working-class heroes like Lanah Sawyer are rarely remembered.

To me what is most extraordinary is that we can recover as much of her story as we can—because she, unlike most survivors of sexual assault then and now, came forward, pressed charges, and made her story so compelling that one of the spectators at the trial decided it was worth publishing a detailed account of the proceedings. It was the first such report of a rape trial in American history. Without it we would know little more than Lanah Sawyer’s name.

Of course there is so much we don’t know—she didn’t leave behind a portrait that would tell us what she looked like; she didn’t leave behind letters that tell us something of her inner emotional turmoil. In part that was because of her age and her class and her gender. But it was also, clearly, because she didn’t seek the spotlight.

At the same time, one of the most troubling aspects of rape culture then, as now, is that the cases that attracted public attention were almost always those that involved elite men. “Life of a citizen is in the hands of a woman,” cried one of Henry Bedlow’s attorneys. As though a rapist’s social standing should protect him from consequences. As though a woman didn’t deserve legal recourse.

Recently, the philosopher Kate Mann described this phenomenon as “himpathy.” Lanah Sawyer’s story is an opportunity to pause and reflect.

Why do we focus so much on what elite male perpetrators stand to lose if they are held to account—rather than on what their victims have already lost? How does a sexual assault, how does sexual harassment in the workplace, change a woman’s life? We know remarkably little about those stories.